In brutal aesthetics, however, the animal mutates variously into a beast, a god, a monster, or a creature.[i]

Brutal aesthetics is not nihilistic, it is only the first step. To illuminate, to connect, to transform, to reanimate is the important thing.[ii]

We made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over. (James Baldwin)

The second installment of my critique of The Vegetarian continues to dig into the main issues and to enjoy the curious pursuit of meanings of the estranged young woman who wishes to escape life among the human fold. In my first essay, I would have wished to see a challenge to my description of Part 1: “The Vegetarian” as somewhat inelegant prose with clichés of bloody horror in the repetitive dream vignettes. Perhaps the blandness of the first part is deliberate as an expression of the poor mind and empty heart of its narrator Mr. Cheong. Unimaginative, he sees the world as a puppet theater, a shadow play of flat two-dimensional human beings in whom one does not invest much of his own disinterested being.

In the work as a whole, I see avant-garde artistry in a larger element than just the composition and prose. Overall, there is much repetition in the return to scenes of critical importance that is beyond any consideration of clichéd imagery. Han Kang, whatever may be the aberrations of the translation from Korean into English, centered her novel about a surreal situation of a tormented woman. One can hardly call Yeong-hye the protagonist, though she is pivotal in her catalyst role. Han chose to narrate the story in an unusual structural style. (I recall one critic claiming the author violated rules of composition by mixing or switching points of view. Such changes of POV, though, especially if there’s a purpose for different angles of perception, are not uncommon in artistic writing. (The variations of POV did not upset the Man-Booker judges.) Few non-academic readers these days will go deep in studying this novel. A composition of three stories in one, each part informs the reader from a different person’s point of view; each part reflects back on the brutal family crisis at the dinner party, which changed the lives and relationships of each of the family members. Suicidal thoughts are entertained by several characters. Also the violent and cruel assaults on Yeong-hye are described as brutal facts, such that her sufferings are quite off-putting for the best-seller pleasure-reading public. This is literature for readers with steely nerves. And it deserves a second close reading. How many want to reread a complicated, mosaically structured work, especially a work that aims to disturb and perhaps displease? Its conclusion is ambivalent at best.

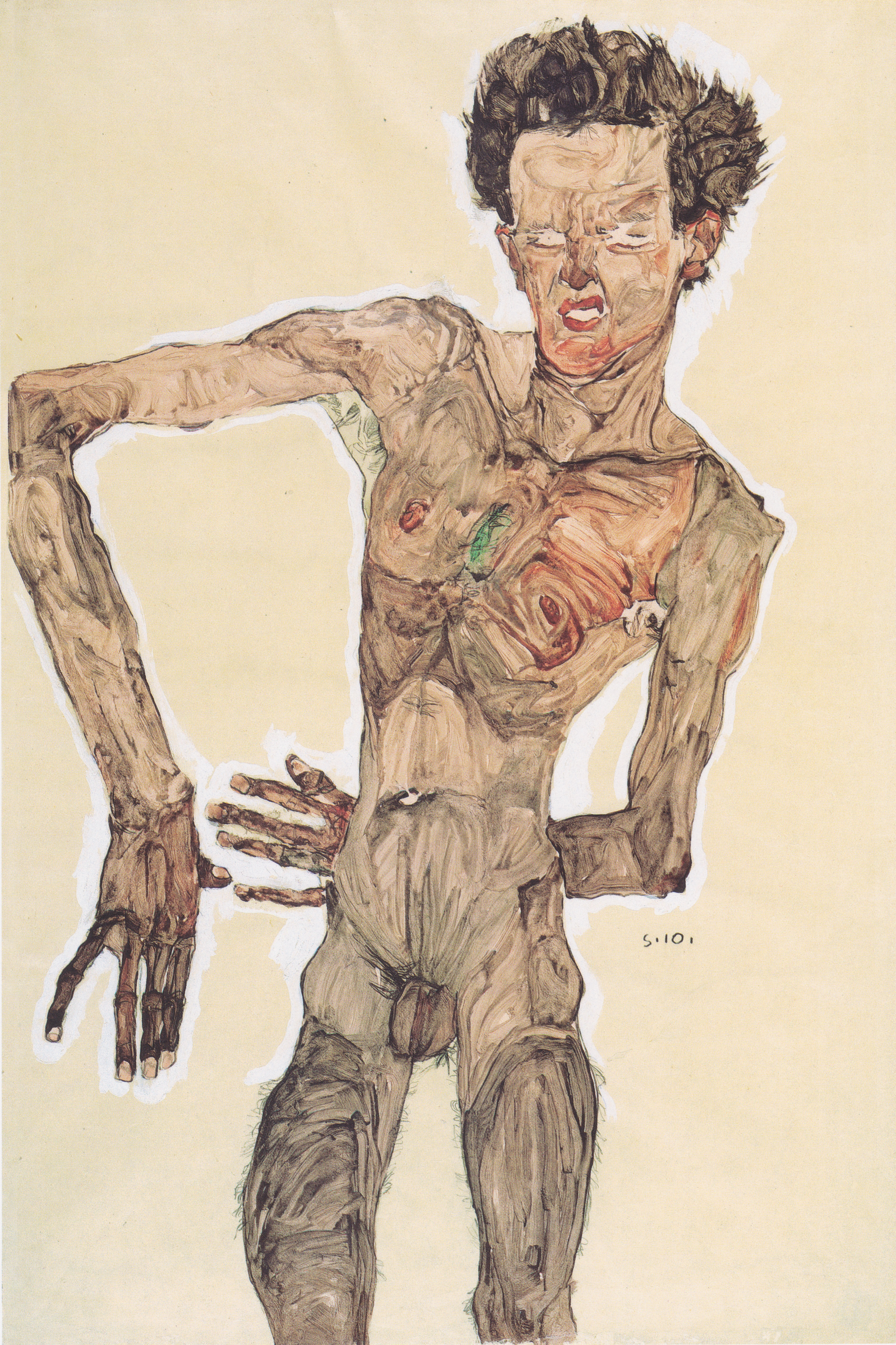

Brutal Art of Ego Schiele

In his opening remarks of TRMBC’s June discussion, Bill Hagens invoked the name Egon Schiele, a painter of the later fin-de-siècle Vienna. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egon_Schiele) The mention of the artist in this regard was an uncanny coincidence. The name went off like a small explosion in my thoughts. Only two hours before our 9:00am discussion, I brought up Egon Schiele’s name with Peter Farnum as we sat and talked over coffee. I was thinking of unusual images like the emaciated figure such as Yeong-hye had become in her dislike of eating. In fact, we looked at some images of Schiele’s drawings and painted portraits, depicting extraordinarily skinny, boney, angular nudes of his female models and some contorted self-portraits of the exceedingly thin artist himself.[iii]

Whether in his angular nakedness

Figure 1

By Egon Schiele – repro from artbook, Public Domain, Link

or dressed in a suit (see in other images of the Wikipedia site), Schiele painted himself in numerous portraits, often awkwardly posed as a scary wraith of a human being, contesting the normal values of a healthy human torso, eyes staring boldly at the spectator, drawing the viewer in to examine in detail the contorted, skeletal human form. The torso appears almost transparent, showing through to bones and organs. His female figures also hold the spectator’s gaze by their own blank-eyed stares, compelling for the moment that the viewer inspect the pale, skeletal anorexic torsos, the withered breasts and nipples of bodies barely clinging to fleshy, carnal existence.[iv]

Figure 2

By Egon Schiele – Christie’s, LotFinder: entry 5812222 (sale 1532, lot 32), Public Domain, Link

The pubic zone with exposed vulva is often a focus of his model’s pose. I would call many of Schiele’s works raw, naked representations, unnerving as artistic images, hardly intended for conventional pleasurable viewing. Unconventional, cruel and alarming as the images are, the aesthetic at work is without doubt avant-garde artistry. The Viennese artist is “brutal” in my definition because he appears to enjoy confusing the viewer with ambivalent or transgressional values, in the same way that Francis Bacon with his screaming, gaping popes and disfigured, caged, bloody portraits is defying the viewer to take pleasure in his forms. Surely Bacon is asking the viewer to be shocked into an awakening.[v] What is the gaping face supposed to be shouting or saying?[vi] The viewer is as much repelled as drawn in. Shocking effects are at work in Hang Kang’s story. The problem with facing the fact of the shock is that one seldom hears from readers who have given up reading from revulsion.

In her depictions of Yeong-hye, Han is offering the reader a disturbing image of a cruelly exploited woman in a patriarchically dominated society. Driven to distraction, she is anxious to depart from a carnivorous diet to that of minimalist vegan, not motivated, as one might expect, by romantic morality, scientific nutritional concerns, nor by sentimental, political or animal-rights ethics, but by the shock of a hellish dream. For this change, Yeong-hye finds herself cruelly treated by her husband, his friends, and her own immediate family. The husband, since courtship, has been mostly emotionally and psychologically disinterested in his wife; He just married because he needed a wife; he married her as a badge of normalcy so that she serve his every need, as he imagined husbands and wifes normally played their roles. What shocks is her mistreatment by other family members, through irrational, sadistic psychological and physical violence.

Something is gravely missing. That there is no calm, educative talk, no kindness or persuasive counsel offered her by her husband and her family seems to establish the pattern of abusive behavior she has grown up with, against which now Yeong-hye passionately rebels. Yet more radically, as Yeong-hye grows anorexically thin and perhaps malnourished, she does not suffer, but actually desires to experience a change of life from carnal humanity into sap-filled arboreal nature. She wants to become and to live as a tree. Her change is radical, for it means a total break from the pattern of past life, a desperate wish to reclaim her own being and full control of her body. Human culture, as it has beaten her down, has offered her no place to live comfortably. Her change, a desired metamorphosis, is one that astounds her husband and family. Are they angry just because she is breaking some law of conformity, perhaps, in their minds, some law of normal family respect? Do they think her mad to buck society’s norms? Do they think they can act like gods, to dominate, nay, own, her being?

Reincarnation

To reanimate oneself literally, or to reenchant oneself psychologically, into another non-human species is a type of “reincarnation” as the Hindus, the Pythagoreans, and the Platonists philosophized. It smacks of mythology and mystical thought. In Han’s novel there is little hint of any theological explanations, but there does appear to be a sacral or sacrificial element in Yeong-hye’s desire to give humanity up. In modern realist literature, it is hardly a normal, certainly not a traditional transformation. An early Veda explains reincarnation as follows:

“The eye must enter the sun, the soul the wind; go into the heaven and go into the earth according to destiny; or go into the water, if that be assigned to thee, or dwell with thy limbs in the plants.”[vii]

The Emaciated Woman

Though Yeong-hye cooked ably for her husband in former days before her turn to vegetarianism, without meat she noticeably changed her features. In Mr. Cheong’s words:

“She grew thinner by the day, so much so that her cheekbones had really become indecently prominent. Without makeup, her complexion resembled that of a hospital patient. If it had been just another instance of a woman’s giving up meat in order to lose weight then there would have been no need to worry, but I was convinced there was more going on here than a simple case of vegetarianism.” (p. 23)

Ever since the horrific dream of butchery in the red barn which Yeong-hye claimed was the sole motivating reason she withdrew from the omnivore diet, she became lean and then emaciated. Mr. Cheong informs the reader:

“All because of this agonizing dream, from which I was shut out, had no way of knowing and moreover didn’t want to know, she continued to waste away. At first she slimmed down to the clean, sharp lines of a dancer’s physique, and I hoped things might stop there, but by now her body resembled nothing so much as the skeletal frame of an invalid.” (p. 25-26, italics in text)

Wasting away like an invalid did not seem to disturb her unwitting husband. Yeong-hye, the passive Mr. Cheong informs us, had become something of a ghost to him before this time, but once she had begun her transformation to vegetarianism, after she had told him her horrific dream of bloody meat and the “strange uncanny feeling,” she began to grow distant from him, unconcerned about their marital relationship. Her eyes grew vacant, and her husband noticed the growing distance by her unconscious stare or gaze. After the rude and brutal rape of his wife, which the reader can receive only in disgust, Mr. Cheong notices her blank stare:

“I grabbed hold of my wife and pushed her to the floor. Pinning down her struggling arms and tugging off her trousers, I became unexpectedly aroused. She put up a surprising strong resistances and spitting out vulgar curses all the while, it took me three attempts before I managed to insert myself successfully. Once that had happened, she lay there in the dark staring up at the ceiling, her face blank, as though she were a ‘comfort woman’ dragged in against her will, and I was the Japanese soldier demanding her services.” (p. 38)

Some readers might well conclude that mental dysfunction is at work in Yeong-hye and that her disease is showing distinct signs of anorexia. However, this psychological problem is not woven into the story in any meaningful way. It is overlooked by other characters. The doctor is not sure exactly why Yeong-hye refuses to eat. Very late in the story diagnostic terms such as “anorexia and “schizophrenia” are mentioned by her doctor at the sanatorium.[viii]

“Only the violence is vivid enough to stick.” … “Violent acts penetrated by night.” (p. 35)

The lines above are expressions from Yeong-hye’s dreams. What are readers to make of these dreams? The critic may be urged by them to regress into old-fashioned Freudian interpretation, making connections with parental figures, symbolic imagery, and deeply internalized emotions. This may be the subject of some future graduate student’s literature paper: “The Dream Sequences in Han Kang’s Novel The Vegetarian Analyzed in Accordance with Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.” Oliver Saks, in our day, may be the person to whom would turn for illuminating explanations. In light of the family dynamics at work in the story, I think it is quite possible to make some intrinsic connections between the dream actions and imagery and other personal interactive motifs of the story, but my statement that the dreams intend to horrify, to impress the reader with awful tortures of previous life, and to inform the reader of Yeong-hye’s disturbed psyche about torture, blood, butchery, food, and other distasteful matters is to describe them well enough. In the course of this commentary (in future essays), I will make further reference to these dreams as I need in order to indicate certain motifs.

However, to return to the rape described above: the rape scene clearly fits into the series of brutal acts we learn from the narration of Mr. Cheong himself. The dreams–hallucinations–are vignettes in italics, presumably the interior narration by Yeong-hye herself, interruptions interspersed with the foreground first-person narrative. The first part is distinguished from the second and third parts by its first-person point of view, a position of power. Various violent acts detailed in the chapter as real events may be taken into account as “vivid enough to stick.” That is, to stick vividly in Yeong-hye’s psyche and in the minds of readers. Yet, they are narrated by a very insensitive, uncaring man, who, though submissive to his bosses and colleagues at work, makes up for his impotence by lording his power over his wife. For the most part, the husband seems unaware of just what hideous truths he is artlessly exposing about his own nature. Uncomfortable as life had become with Yeong-hye’s wasting away, the husband expresses deep ignorance in not wanting to know what was at work in her troubled mind:

“Even given the extreme unpredictability of her condition, I wasn’t prepared to consider taking her for an urgent medical consultation, much less a course of treatment. There’s nothing wrong with her, I told myself, this kind of thing isn’t even a real illness. I resisted the temptation to indulge in introspection. This strange situation had nothing to do with me.” (p.26)

Therefore, I asked myself: Am I simply to accept Yeong-hye’s husband and her family as supremely ignorant, unkind people? They are that. In times of food shortages, such as war times, it was deemed necessary to eat whatever one was offered and children did not escape being forced to eat everything served on a plate. (After World War II, I experienced this in England’s austere rationing of foods.) However, Yeong-hye is a grown woman. Are the mother and father offended by their daughter’s refusal to eat out of being shamed by her malnutrition? Mostly it seems that Yeong-hye’s bucking their parental demands is the reason for their anger and violent display against their obstinate daughter. They have the power. They makes the rules.

Butchery

Yeong-hye is not loved nor regarded highly by Mr. Cheong for any admirable feminine traits, though she possesses a lively energy and an ability to prepare suitable dishes for dinners. He admired her for her skill with the carving knife and the butcher’s hatchet as her mother had taught her:

“I’d seen my mother-in-law gut a live fish, and my wife and her sister were both perfectly competent in hacking a chicken into pieces with a butcher’s cleaver. I’d always liked my wife’s earthy vitality, the way she would catch cockroaches by smacking them with the palm of her hand. She really had been the most ordinary woman in the world.”(p. 26)

Just as the dreams have impressed Yeong-hye with a disgust of meat, it has to be understood that a violence precedes butchery. All imply penetration, the blood emits from cuts, piercing and wounds. It is a fact in the preparation of blooded meats, fish, fowl or mammal, that a killing takes place, innards are gutted or cleaned from the body cavities. In many cases the body of a slaughtered and bloody animal is hung to bleed out. Much of this violence is hidden from the reader, but it is implied, and the disgust is most explicitly evoked in the dream passages. These are also the most elaborate narratives that come from Yeong-hye’s secret, interior life. For example, in Dreams # 4 and #6:

“Saliva pooling in my mouth. The butcher’s shop, and I have to clamp my hand over my mouth. Along the length of my tongue to my lips, slick with saliva. Leaking out between my lips, trickling down.”(p.40)

“Something is stuck in my solar plexus. … I can feel this lump all the time. … The animals I ate have all lodged there. Blood and flesh, all those butchered bodies are scattered in every nook and cranny, and though the physical remnants were excreted, their lives still stick stubbornly to my insides.”(p.56)

Penetration

Therefore, one of the motifs of the brutality forced upon Yeong-hye is the act of penetration: in her dreams (Dream #1) she imagines bloody meat pierced by a bamboo stick, and meat pushed into her mouth; (Dream #2) a finger is stuck into her mouth; (Dream #4) a finger sticks into an eyeball; (Dream #5) a dog bites a young girl’s leg. As described above, her husband penetrates her sexually without her permission; her father attempts to force a piece of meat into her mouth, first with chopsticks, then with his fingers; she cuts or stabs her own wrist with a fruit-knife, and IV needles are inserted in her arm in the hospital. Besides the violence of penetration, Yeong-hye has been abused throughout her life by whippings from her father, even until the age of eighteen. At the dinner with her husband’s company, the frail Yeong-hye is put through humiliations by the wives of the bosses. A particularly ugly remark is made by one of them:

“Imagine you were snatching up a wriggling baby octopus with your chopsticks and chomping it to death—and the woman across from you glared like you were some kind of animal. That must be how it feels to sit down and eat with a vegetarian!” (p. 32)

The author is taking great pains to impress us with acts of violence; surely we are not to merely turn away repulsed but to consider how prevalent these awful acts have been in the life of Yeong-hye. These acts are not some pagan tortures of a Christian martyr, however one might think them comparable to the sufferings of one who has broken some inviolable law.

And not to be forgotten is Mr. Cheong’s own butchery dream of stabbing someone and pulling from the cavity the “long, coiled-up intestines. Like eating fish, I peeled off all the squishy flesh and muscle and left only the bones.” (p. 57) Did he wonder whether his wife was the subject of his stabbing? In the dark of morning, trembling inside, he pulled the covers from his wife sleeping in the hospital bed, and felt for the moist blood and intestines. In touching her philtrum, he was testing her breathing to discern whether she was alive or not. (p. 57)

Are these brutal acts so usual in literature that we readers should not feel repulsed? Cruel, sadistic acts and bloody dreams are descriptions of much that we have come to expect and accept as horrific in literature and film. The acts are narrated by Mr. Cheong, himself a figure of loathing. Do we just get used to the horror, so inured that we give up objecting to the normalizing of such cruelty? Will blood and power (See Addendum below) continue to be the privilege of those who feel no regrets in wielding the right? Other traditional power figures are Yeong-hye’s physically violent father and unsympathetic mother. These figures belong to the old myths and traditional themes of literature. Traditional they are and belong to the past. How does society get beyond this abuse of power?

What is the reader to think?

True, in this novel, there is, as Mr. Cheong says, more going on than a simple case of vegetarianism. He informs us openly, blatantly what he beholds in Yeong-hye, and most of his views are without feeling, in fact, barbaric. Her human nature as a woman and wife is beyond his ken. Thus something beyond the normal person’s ability to comprehend is needed: Yeong-hye no longer fits in the mythology of human transformation. Perhaps it is the reader’s job to discover what the important point of this transformation might be. If it is a surreal delusion or hallucination, it is still necessary to analyse–psychoanalyse?–Yeong-hye’s illness, to grasp the meaning of her irrational desires. Art is surely intended to awaken us to new ways of thinking, to vibrations of things yet to come. How to explain the extreme antipathy towards her, of her husband, her family and other members of society? How does one resolve the ongoing rounds of violence of power figures’ exploitation and impairment of the vulnerable person’s life? The estrangement forced upon her takes on the appearance of an allegorical hatred. Why cannot Yeong-hye have control of her own body and do with it as she pleases?

In the sanatorium (Part 3: “The Flaming Trees”), In-hye, the submissive, obedient sister, expresses such a thought about freedom and the body as a revelation after she beheld the failed force-feeding of Yeong-hye. Having collapsed in the bathroom and vomited after experiencing the cruel treatment of her sister, In-hye asserts:

“It’s your body, you can treat it however you please. The only area where you’re free to do as you like. And even that doesn’t turn out how you wanted.” (p. 182)

All the other members of her family seem to think Yeong-hye should not break free from unspoken laws by which they live. She is not just being non-conformist, she is in some way transgressing a sacred law they wish to preserve. It is no wonder Yeong-hye seeks a total transfiguration to escape the traditions others wish to preserve and live by.

The Closing Scene: The White-Eyed Bird

The final scene of Part 1 has its own note of violence when Yeong-hye has fled from her hospital room to the dry fountain in the courtyard. For her husband who will soon divorce her, she presents a very puzzling element that must confound the reader just as it does the husband. Mr. Cheong finds her as follows:

“My wife was sitting on a bench by the fountain. She had removed her hospital gown and placed it on her knees, leaving her gaunt collarbones, emaciated breasts and brown nipples completely exposed.”

Then he approaches her (note the attention to body parts) and sees that her mouth is smeared with blood, as if it were poorly applied lipstick. He thought to himself that he did not know this woman. He admits the bald truth of this thought. As he draws close to her, he sees something incomprehensible:

“I prized open her clenched right hand. A bird which had been crushed in her grip, tumbled to the bench. It was a small white-eyed bird, with feathers missing here and there. Below tooth marks which looked to have been caused by a predator’s bite, vivid red bloodstains were spreading.”(p. 60)

What does the reader make of this event and what appears to be, in the mangled bird that a cat might have caught, the emergence of old-fashioned symbolism? A scene of mysterious, inexplicable horror. In this situation, Yeong-hye has shown something of her creaturely nature, a wildness. She has gone beyond the normal human self and ventured into the wild. One might say, she has snatched the soul from her body and torn it apart. She has become a different being. In one of the Yeong-hye’s dreams such a throttling death of an animal is recounted:

“Dreams of my hands around someone’s throat, throttling them, grabbing the swinging ends of their long hair and hacking it all off, sticking my finger into their slippery eyeball. Those drawn-out waking hours, a pigeon’s dull colors, in the street and my resolve falters, my fingers flexing to kill. Next door’s cat, its bright tormenting eyes, my fingers that could squeeze that brightness out. … I become a different person, a different person rises up inside me, devours me, those hours . . .” (p.40)

It really is mystifying what one can make of these connections, but how often does one stop reading, look back through passages to find such oddities? There is a disordered jig-saw puzzle nature to the parts of the novel. However, one fact the reader does come to understand is that Yeong-hye is not the only character who suffers a life-shattering transformation. (I will consider this development of other characters in a later essay.)

Now I have had much time to sit back and ponder the bizarre nature and purpose of Han’s writing, that she sees family and social life of the modern world one of suffering and violence. In the relationships in The Vegetarian, she exposes a general a lack of respect for each person’s otherness; a failure to communicate openly indicates a fear to inform others in order to express freely one’s thoughts and feelings, to explain through educative conversation one’s own personal nature. Hers is a story of things not just falling apart, but having fallen apart.

As a solution for her own dilemma to regain power for herself, Yeong-yhe’s desire is to wipe the slate clean, to start afresh, through regenerative transfiguration or transmogrification into a wholly different being. Trees seem less cruel to one another than human beings. Really, what does one do when one’s personal life is impossible to bear? Is it enough for a modern realist to write stories about people making do, coping with a gradual deterioration of living in a society that obviously seems to be hurtling into barbarism? Brutal aesthetic artists aren’t choosing the model of retreating into passivity and calmly meditating till the suffering is done. They seem intent on moving ahead of the losing program, hastening beyond the tedious life of waiting and watching as the violence of wars, weathers, famines and extinctions rages just beyond the threshold, and seeking a vision beyond humanistic nature as we know it. Civilization and humanism have not prevented calamity and catastrophe, but, instead, have helped bring us to the state we are in. We need a brutal regeneration, a reanimation, a transformation.

Addendum: References to Some Ideas of Walther Benjamin

[In this striving for a rational argument about what ameliorative or remedial actions can be taken to resolve this pernicious pattern of life, I have read Walter Benjamin’s (1892-1940) famous essay “Critique of Violence.”[ix] Benjamin sees no way of regressing to a remedial point of cultural change; small, progressive steps to better humankind in the mythical patterns and management of established laws are impossible. Therefore, he suggests a remaking of the laws, fresh, creative changes not tried before. Jürgen Habermas in “Consciousness-Raising or Rescuing Critique” speaks of Benjamin’s idea as a rescuing critique, which constitutes “a punctual breakthrough from the continuum of natural history.” This is termed by Benjamin “a ‘divine’ or ‘pure’ violence that aims at ‘breaking the cycle under the spell of mythical forms of law.’”[x] In various essays by commentators, Benjamin seems to have a renewed life almost a century after his early period of critical writings. Furthermore, Benjamin’s essays and ideas regarding the law-making violence of radical revolutionary strategy have been employed for their unusual ground-breaking argument in various papers or presentations (See, footnote 1 above, regarding Hal Foster).[xi]

I wonder if it is our own deplorable state of civilization that warrants a look backward to writers who spoke of not continuing with the failed traditions of power and domination, with all the wreckage and ruin that never seems to be mitigated or remedied, but of a cleansing renewal. The following passage from Benjamin’s letters speaks to that end:

“On this planet great civilizations have perished in blood and horror. Naturally one must wish for the planet that one day it will experience a civilization that has abandoned blood and horror; in fact, I am … inclined to assume that our planet is waiting for this. But it is terribly doubtful whether we can bring about such a present to its hundred- or four-hundred millionth birthday party. And if we don’t, the planet will finally punish us, its unthoughtful well-wishers, by presenting us with the Last Judgment.”[xii]]

David Gilmour, December 18, 2018

Footnotes:

[i] These statements on Brutal Aesthetics come from Hal Foster who delivered The Sixty-Seventh A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts: “Positive Barbarism: Brutal Aesthetics in the Postwar period, Part I: Walter Benjamin and His Barbarians” (April 18, 2018).

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Many images can be found by Google-ing his name with the Image rubric highlighted.

[iv] See for example: https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4183/34655744765_8748b02b58_b.jpg.

[v] “I think that life is violent and most people turn away from that side of it in an attempt to live a life that is screened. But I think they are merely fooling themselves. I mean, the act of birth is a violent thing, and the act of death is a violent thing. And, as you surely have observed, the very act of living is violent.” Francis Bacon from David Gruen, The Artist Observed: 28 Interviews with Contemporary Artists.

[vi] Francis Bacon, with some other quotes, can be reviewed in: https://www.theartstory.org/artist-bacon-francis.htm.

[vii] From the As’vayalana Grkyasustra as quoted in Peter Watson’s Ideas from F.G.S Brandon (editor), The Savior God (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1963), p. 86.

[viii] To In-hye the doctor speaks: “I know I told you this last time, but fifteen to twenty percent of anorexia nervosa patients will starve to death.” …”But Kim yeong-hye’s is one of those particular cases where the subject refuses to eat while suffering from schizophrenia. We were confident that her schizophrenia wasn’t serious.” (p.146)

[ix] Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, translated by Edmund Jephcott (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, c1978) p. 277-300.

[x] Habermas quotes from Benjamin’s Reflections (p. 300), in his essay in the collection On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, edited by Gary Smith (Cambridge, Massachussetts: MIT Press, c 1988) p. 90-128.

[xi] A recent thesis on aesthetics of violence which offers an expanded explication of Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” can be found on-line: The Violence of Aesthetics: Benjamin, Kane, Bolano by Nicholas A. Fagundo University of Western Ontario, (September 2013) in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 1561, see https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1561. See “Chapter 1: Transgression, Violence, Aesthetics: Point of Departure.”

[xii] In Hannah Arendt’s “Introduction” to Illuminations (cited above), p. 38.